1. Introduction

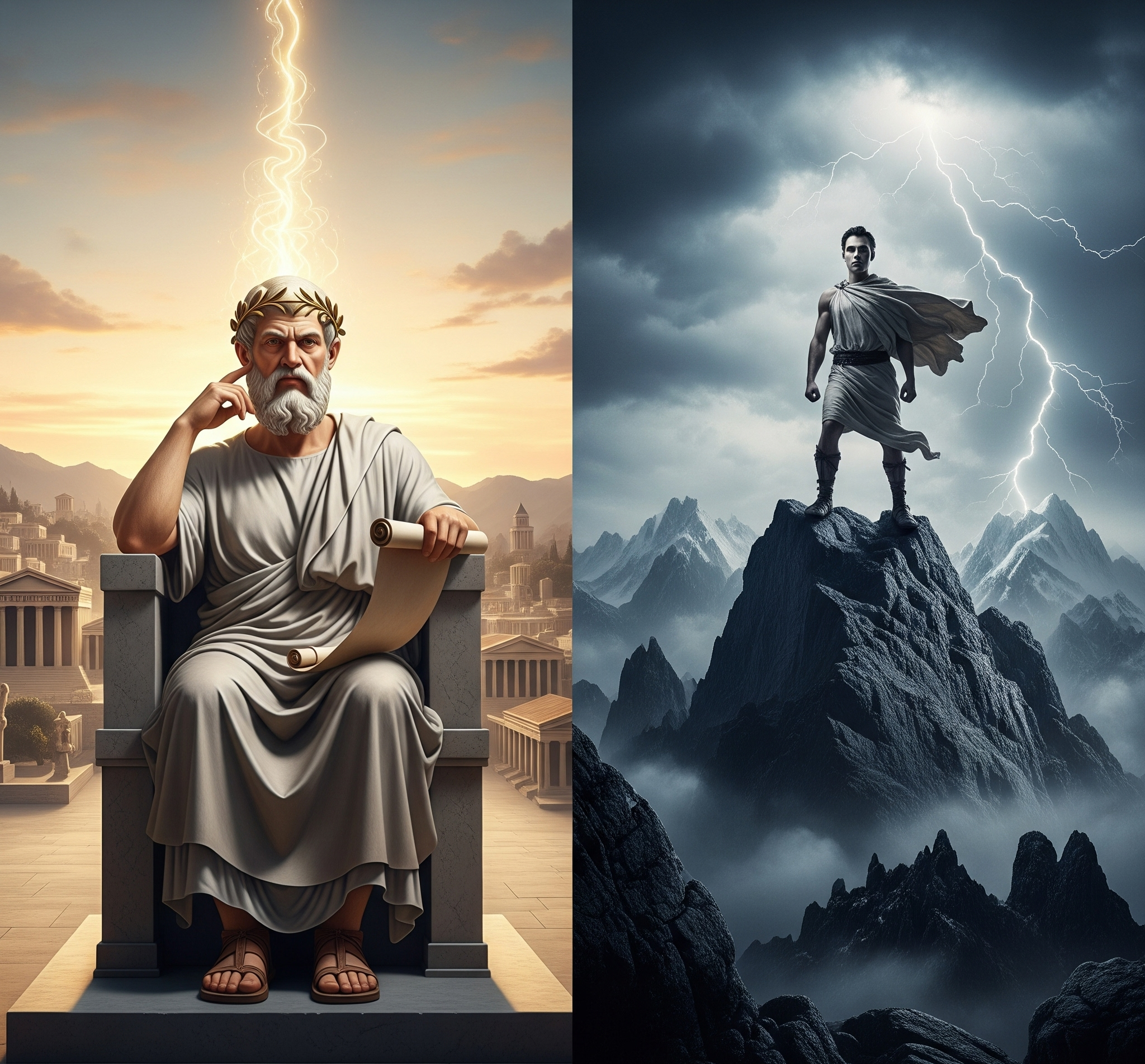

The question of ideal human excellence and its role in shaping political and social order has been a perennial concern in Western philosophy. This article embarks on a comparative analysis of two profoundly influential, yet strikingly divergent, conceptions of such excellence: Plato’s Philosopher-King and Friedrich Nietzsche’s Übermensch. Both ideals emerge from significant intellectual and cultural crises, grappling with the waning authority of established frameworks and proposing radical new trajectories for human flourishing and societal organization. This article will, therefore, compare and contrast the two perspectives under the auspices of a dialogical exchange, examining the strengths and weaknesses of both positions and outlining their implications for contemporary discourse on issues of power.

The succeeding sections will first establish the conceptual frameworks of each ideal, detailing their origins, key traits, political visions, and metaphysical underpinnings. Subsequently, a comprehensive comparative analysis will be undertaken, evaluating these ideals in terms of their grounding, feasibility, compatibility with the modern world, and ethical-social consequences. The article will conclude by summarizing key insights and suggesting avenues for future inquiry into these enduring philosophical challenges.

2. Conceptual Frameworks

2.1 Plato’s Philosopher-King

2.1.1 Origins in The Republic

Plato’s conception of the Philosopher-King is most fully articulated in his seminal work, The Republic. This dialogue represents a thorough examination of the nature of knowledge and reality, interweaving questions of ethical, political, social, and psychological importance with metaphysical and epistemological considerations. The central problem Plato seeks to address is the necessity of ensuring the rule of philosophic reason and restraining both the populace (demos) and the warrior class to establish a just political order.

The provocative thesis that initiates the discussion of the Philosopher-King is: “Until philosophers rule as kings or those who are now called kings and leaders genuinely and adequately philosophize… cities will have no rest from evils, nor will the human race”. Plato’s ultimate aim in The Republic is to demonstrate that proper psychic rule is identical to proper political rule and that his candidate for justice exists both in poleis (cities) and in psyches (souls). This vision entails a society where everyone practices the function for which “his nature made him naturally most fit”. Plato divides citizens into three estates, the philosopher-kings (or rulers), the guardians (also known as auxiliaries or the military estate), and the producers (or workers) creating a hierarchical and pyramidal social structure, with a primary emphasis on the unity and self-sufficiency of a well-structured city, rather than solely on the well-being of the individual.

2.1.2 Key Traits and Characteristics

The Philosopher-King is fundamentally characterized as a lover of wisdom (philosophoi). They are selected from the ranks of the guardians and undergo an extensive and rigorous curriculum of higher learning designed to prepare them for an ascent from the world of the senses to the world of intelligence and truth. This ascent is famously summarized through the similes of the Sun, the Line, and the Cave. The education program includes a preparatory schooling of ten years in “liberal arts” such as arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and theoretical harmonics, followed by five years of training in the “master-science of ‘dialectic’”. This dialectic aims to enable the philosopher to systematically engage with the Forms, especially the “Form of the Good,” which is the principle of goodness for all else.

Upon successful completion of this rigorous training, candidates are sent back into the “Cave” to serve as administrators of political life for 15 years. Only at the age of fifty are they permitted to primarily pursue philosophy, though even this pursuit is interrupted by periods of service as overseers of the state. Their rule is considered legitimate because they alone possess the knowledge of how best to rule, grounded in their understanding of the Forms. Plato envisions the Philosopher-King’s life as a “mixed life of ruling and philosophizing,” arguing that this is the best possible life available to a wisdom-lover, as a life of pure philosophy is deemed “too high for a human being”. Plato acknowledges that virtues involve emotional attitudes, desires, and preferences, not just technical skills, and seeks to coordinate these rational and affective elements. The ideal character fostered through primary education for the ruled psyche is one that is moderate in appetites, truth-loving, loyal, and courageous.

2.1.3 The Political and Social Vision

Plato’s political vision is one of an autocratic rule by an aristocracy of the mind. The state’s fundamental goal is the flourishing and happiness of the whole city, ensuring that every estate achieves the part of happiness intended for it by nature, rather than prioritizing the happiness of any single estate. This division of functions, based on natural aptitude, is intended to guarantee a high degree of efficiency and to secure internal and external peace, which was a significant achievement given the constant threats of interstate and civil wars in ancient Greek society.

The hierarchical social structure is pyramidal, with the philosopher-kings at the apex, a military estate for defense and internal security, and a broad, lowest estate comprising workers who fulfill the vital needs of society. Crucially, Plato does not view the two lower estates as merely instrumental; rather, he explicitly states that their well-being contributes to the flourishing of the entire city. This social order is founded on the “fundamental inequality of men and of parts of the soul,” which Plato asserts exists by nature and forms the basis for the order of rank and differences in worth among individuals. To maintain this order and secure the authority of philosophy, Plato suggests that the good city must be founded on “noble lies” of divine origin, including poetic lies about immortal souls judged by just gods. Within this structure, the philosopher-king, through their reason and aspiration, directs the productive activities of others, ensuring that their appetitive and spirited desires are optimally satisfied by the order they establish.

2.1.4 Metaphysical Grounding

The entire Platonic ethical and political framework is underpinned by a robust metaphysics. Central to this is the “Form of the Good,” which is posited as the ultimate source of all being and knowledge. Plato asserts that not only do the objects of knowledge owe their being known to the Good, but their very being (ousia) is also derived from it, emphasizing that the Good is “beyond it (epekeina) in rank and power”. This Good is understood as an intelligent inner principle that determines the nature of every object that is capable of goodness, enabling them to fulfill their respective functions appropriately.

The philosopher’s knowledge of this ultimate Good provides a solid basis for the good life of the entire community, as well as for its majority, as all benefit from the good order of the state derived from this principle. The goodness of the individual soul itself is explained as a smaller copy of a harmonious society, reflecting this cosmic order. For Plato, genuine knowledge extends beyond merely comprehending objects’ identity, difference, and interrelations within a given field; it also necessitates understanding the internal unity and complexity of each entity. The attainment of this “superhuman state,” as it is described in the Theaetetus, is contingent upon an individual’s readiness to engage in strenuous philosophical discourse.

2.2 Nietzsche’s Übermensch

2.2.1 Context in Thus Spoke Zarathustra

Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch, often translated as “Overman” or “Superman,” is as renowned as it is enigmatic. This idea is most famously introduced and developed in his philosophical narrative, Thus Spoke Zarathustra. It is important to note that Zarathustra is not a conventional treatise, and the doctrines presented within it, including that of the Übermensch, should not always be directly equated with Nietzsche’s own views, as Zarathustra’s evolving doctrine sometimes deviates from Nietzsche’s explicit accounts elsewhere. Nevertheless, the Übermensch is considered one of Nietzsche’s “positive teachings” and stands at the very heart of his entire philosophical thought.

The concept emerges in the context of the “death of God,” a profound declaration that signifies the collapse of European morality and Greco-Christian civilization. This event, in Nietzsche’s view, presents humanity with a stark choice: to descend into the state of the “last man” or to strive towards the Übermensch. Thus Spoke Zarathustra aims to create an audience for this novel and challenging teaching, recognizing that such a radical vision would initially find few receptive ears. The work culminates in songs that anticipate the return of Dionysus, symbolizing an affirmation of earthly life and its inherent contradictions.

2.2.2 Core Traits and Values

The Übermensch is defined as a “type that turned out supremely well,” a “higher type” or “type of higher value” in relation to humankind as a whole. This figure is a “value-creating overman, continuously overcoming oneself” through a ceaseless process of creation and recreation, construction and reconstruction of one’s own sense of self and selfhood. Central to this process is the “will to power,” which Nietzsche describes as a dynamic interplay of creative forces involving action and resistance, fundamentally aimed at the affirmation and enhancement of life.

The Übermensch embodies “amor fati,” the love of fate, embracing the doctrine of the “eternal recurrence of the same” – the ability to say “yes” to life, with all its suffering and joy. This means that the Übermensch is tasked with devising “his own virtue, his own categorical imperative,” essentially reversing Kant’s philosophical dictum. This ideal individual is envisioned as a “free spirit” who transcends conventional Christian morality (beyond good and evil), thinking independently of the expectations imposed by origin, milieu, or prevailing opinions of their time. The “new nobility,” a political concept closely associated with the Übermensch, is characterized not by pride of descent but by its orientation towards the future and the cultivation of values such as affirmation of life, strength, health, self-mastery, spirit, free spirit, creative power, magnanimity, and courage. A primary task for this “new nobility” is to counteract “nihilism” through the creation of new values and a new morality, directly stemming from their “will to power”.

2.2.3 The Anti-Structural, Anti-Herd Stance

Nietzsche is a fierce critic of established norms and systems. His philosophical project entails a fundamental campaign against and challenge to all forms of tradition, customs, and institutions, aiming for a radical revaluation of all human values, moving “beyond good and evil”.

Nietzsche harbors a “deep political skepticism” regarding legitimacy, contending that modern pluralist societies, stripped of a consensus on values by secularization, are forced to produce consensus through coercive means and ideological control. He is famously critical of the “will to a system,” viewing it as a “lack of probity”, and is described as an “anti-systematician” who resists imposing systematic frameworks. He denounces democracy, equal rights, and the perceived weakness of democratic institutions, associating them with the “herd mentality”. From his perspective, the state is merely a secularized version of an illusory divine order, and thus, the philosopher of the future must exist beyond its realm. Zarathustra famously advises abandoning the state and civilization, asserting: “Only there, where the state ceases, does the man who is not superfluous begin”.

2.2.4 Symbolism and Autonomy

The “death of God” serves as a symbolic declaration, signifying humanity’s liberation from the dictates, control, and laws of the Judeo-Christian world and other comprehensive doctrines. This liberation paves the way for Nietzsche’s perspectivism, the view that there is no single, true, objective, or universal truth, but rather multiple dimensions, diverse perspectives, and fluid viewpoints. In this context, the “will to power” is understood as having a self-reflective dimension, where power itself becomes an object.

The human subject, according to Nietzsche, is not a fixed, singular substance but is always in a process of continuous creation and recreation, constructing and reconstructing itself as a life project. This drive leads to the establishment of an authentic self-actualization ethics, where the social and political identity of human agency is inextricably linked to its moral or personal identity. While Nietzsche is known for his aphoristic and anti-systematic style, which resists rigid classification, his later thought, particularly from Zarathustra onward, can be seen as a “comprehensive whole shaped and guided by a poetic/musical logic”. He aimed to transcend traditional philosophical distinctions, employing his unique writing style as a form of “musical philosophizing”.

3. Comparative Analysis and Evaluation

3.1 Grounded vs. Autonomous Ideals

3.1.1 Plato’s Metaphysical Roof

Plato’s Philosopher-King is an ideal intrinsically grounded in a transcendent metaphysical reality: the Form of the Good. This Form is the ultimate source of all being and knowledge, providing an objective and immutable standard for truth and value. For Plato, genuine truth resides in the Forms, and while there is also a “worldly, or phenomenal truth,” the former is primary. The virtues, including wisdom, courage, moderation, and justice, are understood as reflecting a harmonious internal order of the soul and the state, ultimately rooted in this metaphysical structure. This deep grounding provides Plato’s system with a theoretical coherence and consistency that aims to guarantee an objective and stable order, leading to peace within the polis. The philosopher’s “greatest strength” lies in their capacity to “command” and “legislate” based on this access to truth.

3.1.2 Nietzsche’s Existential Horizon

In stark contrast, Nietzsche’s Übermensch operates within an “existential horizon” defined by the “death of God,”signifying the loss of transcendent meaning and objective truth. Nietzsche vehemently rejects absolute truth and objective reality in favor of perspectivism, which asserts that there is no single, universal truth, only multiple interpretations. For him, truth is “anthropocentric through and through” and arises from psychological and social needs, rather than corresponding to an external reality. Human beings are fundamentally “res volens” (willing things), whose existence is defined by self-positing and self-willing, rather than by fixed self-knowledge.

The “will to power” is the central driving force, a dynamic process of creating values and overcoming. Nietzsche’s philosophy is often described as an “(anti-)metaphysics” that, while rejecting the substance of traditional metaphysics, nonetheless redefines its components, including anthropology, theology, cosmology, logic, and ontology, according to his new vision. He conceives of a “world-will” or “will to power” that is synonymous with the motion of all things, highlighting a continuous, dynamic becoming rather than a static being.

3.1.3 Ethical and Psychological Implications

For Plato, the ultimate ethical goal is the just life, which is inherently beneficial for the soul of its possessor. Virtues are understood to integrate both rational and affective elements, striving for a harmonious internal order. Individual happiness is intrinsically linked to the flourishing of the entire city, with philosopher-kings choosing a life of rule as the most fulfilling and best possible for them.

Nietzsche, however, proposes a self-actualization ethics focused on continuous self-overcoming. He emphasizes values like health, strength, and life affirmation, in opposition to what he considers “slave morality” which he deems “life-denying”. From Nietzsche’s perspective, conventional morality is often based on deception and serves to enforce conformity and collective maintenance. He argues that the human self is not pre-formed but is constituted by “agonistic relations” and the ongoing interplay of opposing forces, rather than developing in an isolated internal sphere.

3.1.4 Philosophical Evaluation

From a theoretical standpoint, Plato’s theory of power is presented as more coherent and consistent than Nietzsche’s. His Republic is characterized as a “single sustained piece of philosophical argument,” offering a unified interpretation of its complex themes through consistent epistemological and metaphysical foundations.

Nietzsche’s thought, conversely, has often been critiqued for its perceived contradictions and unsystematic nature, being described as “fragmentary” or “aphoristic”. However, proponents argue that his final teaching, particularly in Zarathustra, forms a “comprehensive whole shaped and guided by a poetic/musical logic,” which operates outside traditional systematic frameworks. His embrace of an “aristocratic radicalism,” which some interpret as a “species of Bonapartism”, presents a deliberately provocative and often paradoxical stance against established philosophical and political norms, challenging traditional logic and valuing creative, aesthetic modes of thought.

3.2 Feasibility and Institutionalization

3.2.1 Plato’s Structured Kallipolis

Plato’s ideal state, the Kallipolis, is designed as a highly structured and institutionalized society. It features a precisely constructed set of political institutions and an extensive system of education intended to cultivate the philosopher-kings. The society is hierarchically divided into classes, with a division of labor based on natural fitness, ensuring that each individual performs the role they are best suited for. This structure aims to provide security, material goods, and foster overall peace and efficiency within the state. Philosopher-kings do not perform all tasks themselves; rather, their role is to direct and coordinate the activities of others, ensuring the optimal functioning of the polis. The stability and legitimacy of this order are, in part, maintained through “noble lies” that persuade citizens of their inherent roles and the divine sanction of the state.

3.2.2 Nietzsche’s Anti-Institutional Ethos

Nietzsche fundamentally rejects the modern state as an end in itself, viewing it merely as a means for the “elevation of the type ‘man’”. He advocates for an aristocratic society founded on a “long ladder of order of rank and difference in worth between man and man,” which he acknowledges necessitates “slavery in some sense”. His “new nobility” is tasked with creating new values to counteract nihilism, driving a “grand politics” of global creation, education, and human breeding, a vision he contrasts with the “petty politics” of nation-states and democracies. While influenced by Plato’s model of a ruling elite, Nietzsche’s aristocracy is based not on inherited descent but on the intrinsic qualities and future-oriented achievements of its members, such as life affirmation, strength, and creative power. He is deeply skeptical of traditional political legitimacy, perceiving states as inherently coercive. His anti-systematic approach and emphasis on individual self-actualization, especially for the rare “higher types,” inherently challenges conventional institutionalization. He foresees an age of war and anticipates the emergence of a “hardened warrior elite” as the crucible for the Übermensch. His political stance is termed “aristocratic radicalism,” emphasizing a profound break with existing norms.

3.2.3 Societal Scalability and Limitations

Plato’s Kallipolis is explicitly designed for the entirety of the city-state, aiming for the happiness and flourishing of the collective. While elitist in its leadership, it envisions a comprehensive societal good, ensuring that all citizens, regardless of their class, find satisfaction in their assigned roles, contributing to the city’s efficiency and peace. Plato’s later works even suggest a movement towards considering the “human herd” as a more uniform flock, implying a broader, if still controlled, applicability of his principles.

Nietzsche’s vision, however, is intensely focused on the cultivation of “a few outstanding individuals” or “higher men,” rather than the human species as a whole. For Nietzsche, the masses are explicitly seen as an “instrument” and “substructure and scaffolding” for the elite. He even states that the “misery of workers must even be increased” to facilitate the production of art and genius. His ideal is not universally applicable; indeed, he suggests that the true individual “who is not superfluous” can only begin to exist “where the state ceases”. This radical elitism inherently limits the scalability and universal applicability of his ideal to society at large, as the majority are deemed merely instrumental to the flourishing of a select few.

3.2.4 Comparative Assessment

In comparing their feasibility and institutionalization, Plato’s vision stands out for its overtly structural and institutional design. He outlines a detailed, hierarchical system with a clear, established order for the collective good, emphasizing education and social roles to maintain stability. Conversely, Nietzsche’s vision is dynamic, revolutionary, and deeply individualistic for the elite, implicitly or explicitly advocating for the destabilization of traditional structures to make way for new values and higher types. While Plato aims for a comprehensive societal good, Nietzsche’s concept of good is primarily reserved for the highest types, viewing the masses as mere means to this end.

While Plato’s model offers a meticulously organized vision for the whole of society, complete with a place for every class and a roadmap for civic harmony, its reliance on the “noble lie” raises significant ethical concerns. The stability of the Kallipolis depends on keeping the majority in deliberate ignorance regarding the true nature of their social position, with the aim of preserving order and security. This mechanism effectively trains the philosopher-king not merely to rule, but to govern through controlled deception. The Form of the Good—Plato’s ultimate ethical reference point—remains abstract, transcendent, and beyond empirical verification. Questions of who truly attains this vision, how it can be recognized, and how faithfully it is applied are left unresolved. In practice, this risks transforming the ruling elite into a class whose supreme skill lies in managing and manipulating the perceptions of the masses. The problem then becomes one of ensuring that such rulers, who hold both authority and epistemic privilege, remain genuinely committed to the welfare of those below them rather than to the preservation of their own power.

By contrast, Nietzsche’s vision, while rejecting such veils and insisting on confronting reality in its most unvarnished form, suffers from an opposite limitation. His anti-institutional ethos makes it difficult to conceive of a stable mechanism for transmitting or cultivating the values he prizes. There is no clear institutional framework for how the Übermensch emerges, no educational model for training them, and no agreed metric for identifying or sustaining them once they appear. The philosophy itself is deliberately resistant to codification, which raises doubts about its durability or scalability. Furthermore, while Nietzsche’s commitment to stripping away illusions can be seen as a call to intellectual and moral courage, it also risks destabilization if the majority are ill-equipped to bear such truths—a concern Plato himself anticipated when warning that the masses, like passengers on an unguided ship, may be incapable of steering themselves wisely. Nietzsche’s ideal thus offers a potent challenge to complacency and mediocrity, yet its feasibility as a sustained social or political order remains uncertain, both in its method of propagation and in its capacity to provide a viable framework for the many, rather than the few.

3.3 Compatibility with the Modern World

3.3.1 Democracy and Political Structures

Plato’s model of “autocratic rule by an aristocracy of the mind” has frequently been criticized as inherently anti-democratic in modern contexts. Nevertheless, some scholars argue that Plato’s arguments, with their “realistic, shrewd observations,” present an intellectual challenge that liberal democracies must “survive” to prove their resilience and legitimacy.

Nietzsche, on the other hand, is an explicit and radical opponent of democracy and egalitarianism. He dismisses democracy as an expression of the “herd mentality” and “misarchism” (opposition against everything that rules). He views modern states as inherently coercive due to their need to manufacture consensus in a secularized world. Despite this, a contentious scholarly debate exists regarding the compatibility of Nietzsche’s thought with democratic theory. Some interpretations attempt to find elements of “agonistic democracy” or “radicalized liberalism” within his work, suggesting that his critique could refine democratic principles. However, critics argue that Nietzsche’s “radically aristocratic commitments pervade every aspect of his project,” making any egalitarian appropriation exceedingly problematic. His philosophy is undeniably that of a “bellicose critic of liberalism”.

3.3.2 Education and Ideal Formation

Plato’s emphasis on education is paramount for the formation of his ideal state and its rulers. He advocates for a rigorous and extensive educational system for philosopher-kings. Primary education is designed to moderate appetites and instill core virtues like moderation, truth-loving, loyalty, and courage, aiming to make citizens perfect in virtue within their designated roles.

Nietzsche, by contrast, is highly critical of modern education’s focus on the “emancipation of the masses”. He argues for a system that promotes the “authority of eminent individuals” through “rigid and strict discipline” for the masses. His vision includes the establishment of institutes of high culture designed to foster a “new aristocracy” and “philosophical commanders,” deliberately maintaining distance from what he considers decadent mass culture. The ultimate goal of this educational approach is the “elevation of man” through the “production of individual great men”.

3.3.3 Social Integration and Impact

Plato’s model promotes social integration through strict stratification, where each individual fulfills their naturally suited role, contributing to the harmony and efficiency of the polis. The state ensures collective preservation and stability, with each part contributing to the whole.

Nietzsche’s vision, however, is rooted in the idea that society’s primary function is to serve the goal of generating “grand individuals and a high culture”. He views humans as being driven to community by a “lack of self-sufficiency” and a need for self-preservation, similar to animals. His “non-egalitarian” stance is seen by some as an “anti-modern provocation or a reactionary utopia”. Furthermore, Nietzsche’s “moral positivism” allows for the strategic use of “lying about the origin of customs” as a powerful tool for political order to secure the emergence of noble and powerful human types, unburdened by traditional morality.

3.3.4 Normative Fit

Plato’s ideal polis aims for universal justice and the “good life” for the entire community, with a clear, albeit authoritarian, commitment to a comprehensive ideal of order and happiness. While his vision can be perceived as “totalitarian” due to its rigid control over individual lives and culture, it is internally justified by its pursuit of an objective Good.

Nietzsche’s “radical non-egalitarianism is in central aspects incompatible with contemporary, mostly egalitarian, political philosophy”. His views challenge modern democracies to reconsider their investment in culture and their promotion of elites. His ideas are often considered “ethically suspect,” particularly in discussions related to colonialism, where his endorsement of it for “therapeutic purposes” is noted. Ultimately, Nietzsche’s project moves “beyond good and evil,” seeking to establish new values that empower “higher types” to live in a world free from the constraints of traditional morality.

3.4 Ethical and Social Consequences

3.4.1 Elitism and Inclusion

Plato’s political philosophy is overtly elitist, advocating for rule by a select minority of philosophers. However, his ideal regime is depicted as “less tyrannical and more paternalistic than typical Greek states”. The “meek” or lower classes are not “viciously abused” but are “reasonably well off,” implying a degree of inclusion and welfare, though they do not rule. While he does not call for the abolition of slavery, he suggests that Greeks ought not to be enslaved.

Nietzsche, conversely, is radically aristocratic and non-egalitarian. He explicitly states that society should be structured such that the masses serve as an “instrument” and “substructure and scaffolding” for “a selected kind of being” to achieve a “higher existence”. His “aristocratic decisionism” entails the authoritative assignment of productive labor to slaves to ensure leisure for intellectual creativity among the elite. Furthermore, Nietzsche’s political vision, particularly as expressed in The Antichrist, chillingly suggests a preference for the “elimination of ‘the weak and the failures’ in order to promote superior life”. While parts of Nietzsche’s thought anticipate totalitarian thought, much of it also undercuts totalitarian ways of thinking, suggesting a complex and often contradictory legacy.

3.4.2 The Non-Ideal Majority

In Plato’s Kallipolis, the majority of citizens (producers, auxiliaries) find their life’s fulfillment and satisfaction in their specific roles and jobs, contributing to the overall efficiency and peace of the city. Their “goodness” and ability to function properly are entirely dependent on the wisdom and direction of the philosopher-kings.

Nietzsche, on the other hand, frequently refers to the majority as “common people” and “mediocre”. He believes they require strict rule and discipline, and his vision is not aimed at improving their condition or “amelioration of their state”. He sees the “slave morality” as a reactive creation of the weak, designed to invert the values of the noble. The existence of the non-ideal majority is thus justified primarily by their instrumental value to the flourishing of the “higher types.”

3.4.3 Effects on the Self

Plato’s philosophy emphasizes the harmony of the soul, where reason governs appetite and aspiration, leading to a just and well-ordered psyche. The principles of unity and self-sufficiency, vital for the city, are also applied to the individual, aiming for an integrated and balanced self.

Nietzsche champions radical individual self-overcoming and self-creation. For him, the self is not a fixed, singular entity but a dynamic “life project,” constantly being created and recreated. The self is not formed in an internal sphere but is constituted by “agonistic relations” – in and through what it opposes and what opposes it. Humans are “res volens” (willing things) who establish themselves not through self-knowledge but through self-positing or self-willing, leading to a state of “sovereign individuality”.

3.4.4 Final Evaluation

Plato’s ideal, while comprehensive and internally consistent, establishes a rigid, hierarchical order primarily for the good of the whole polis. Its reliance on “noble lies” and its instrumental view of the lower classes, despite paternalistic intentions, raise significant questions about individual freedom and potential for repression.

Nietzsche’s vision, conversely, is dynamic and revolutionary for the exceptional individual, offering a powerful affirmation of life and creativity. However, its radical elitism, anti-egalitarian stance, and willingness to sacrifice the majority for the sake of the few present profound ethical and social challenges when considered against modern democratic and humanitarian values. His thought, while valuing individual freedom for the “free spirits,” is often viewed as advocating for a potentially brutal reordering of society where “force gives the first right”.

4. Conclusion

4.1 Summary of Key Insights

This comparative analysis reveals that Plato’s Philosopher-King and Nietzsche’s Übermensch, while both representing ideals of human excellence, embody fundamentally different philosophical approaches to achieving and implementing such ideals within society. Plato’s vision is grounded in a transcendent metaphysics, positing an objective Form of the Good as the ultimate source of knowledge, truth, and moral order. This grounding leads to a structured, hierarchical, and comprehensive political system, the Kallipolis, designed for the collective flourishing and stability of the entire city, albeit under the autocratic rule of a select philosophical elite. Education and the perpetuation of “noble lies” are crucial for maintaining this order.

In contrast, Nietzsche’s Übermensch emerges from an “existential horizon” marked by the “death of God”, leading to a rejection of absolute truth and an embrace of perspectivism and the “will to power”. This ideal is centered on radical individual self-overcoming and value-creation, with an emphasis on strength, life-affirmation, and the “eternal recurrence”. Nietzsche is a fierce critic of traditional institutions, systems, and democratic-egalitarian values, viewing them as manifestations of “herd mentality” or “slave morality”. His vision is not for the masses, who are seen as instrumental to the creation of higher types.

The fundamental difference lies in their metaphysical foundations: Plato’s ideal is tethered to an unchanging, objective reality, while Nietzsche’s is dynamic, self-created, and exists within a world of fluid interpretations. Consequently, their political implications diverge sharply: Plato aims for a stable, ordered society for the good of all (as defined by the philosophers), whereas Nietzsche prioritizes the emergence of extraordinary individuals, even at the expense of the majority.

4.2 Final Position

When evaluating the two ideals, Plato’s theory of power is “more coherent and consistent than Nietzsche’s position”. Plato’s Kallipolis, while authoritarian and elitist, presents a detailed and internally justified model for a stable society, where even the “meek” are “reasonably well off”. His vision, though highly centralized, aims to integrate all parts for the functioning of the whole.

Nietzsche’s Übermensch, while a powerful symbol of individual freedom and self-creation for the elite, is underpinned by a “radically aristocratic” and “non-egalitarian” commitment that is in “central aspects incompatible with contemporary, mostly egalitarian, political philosophy”. His views have been associated with elements of Bonapartism and have been seen to anticipate aspects of totalitarian thought, despite arguments that much of his philosophy undercuts such systems. The “dark side” of Nietzsche’s ideas, particularly his instrumental view of the masses and calls for the “elimination of ‘the weak and the failures’”, raises significant ethical concerns that continue to fuel scholarly debate. As a “bellicose critic of liberalism”, Nietzsche’s ideal often appears at odds with modern democratic values.

4.3 Directions for Future Inquiry

The ongoing scholarly debate about Nietzsche’s political philosophy, particularly its compatibility with democratic thought, remains a fertile ground for future inquiry. Given the ethical complexities, further exploration is needed into how contemporary political philosophy can constructively engage with such radical ideals of human excellence, especially in a post-metaphysical landscape, without succumbing to their potentially destructive implications. Understanding the precise relationship between Nietzsche’s philosophical naturalism and political realism, including how physiological insights might inform political perspectives, also warrants continued investigation. Finally, examining how both Plato’s and Nietzsche’s challenges to traditional authority and their distinct visions for human elevation can inform contemporary discussions on leadership, societal purpose, and individual agency in an increasingly complex world presents a compelling avenue for future research.

5. References

Ansell-Pearson, K. (1994) An Introduction to Nietzsche as Political Thinker. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nietzsche, F. (1886) Beyond Good and Evil. Translated by Walter Kaufmann (1973). New York: Vintage Books.

Kim, A. (ed.) (2019) Brill’s Companion to German Platonism. Leiden: Brill.

Knoll, M. and Stocker, B. (eds.) (2014) Nietzsche as Political Philosopher. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Ansell-Pearson, K. (ed.) (2013) Nietzsche and Political Thought. London: Bloomsbury.

Siemens, H.W. and Roodt, V. (eds.) (2008) Nietzsche, Power and Politics: Rethinking Nietzsche’s Legacy for Political Thought. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Gillespie, M.A. (2017) Nietzsche’s Final Teaching. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lampert, L. (1986) Nietzsche’s Teaching: An Interpretation of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Reeve, C.D.C. (2006) Philosopher-Kings: The Argument of Plato’s Republic. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

Sasaki, T. (2012) ‘Plato and Politeia in Twentieth-Century Politics’, Études platoniciennes, 9, pp. 147–160. Available at: https://journals.openedition.org/etudesplatoniciennes/281 (Accessed: 10 August 2025).

Plato (trans. Reeve, C.D.C.) (2006) Plato’s Republic. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

Nietzsche, F. (1883–1885) Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Translated by Walter Kaufmann (1954). New York: Penguin Classics.

Simpson, D. (1999) Truth, Truthfulness and Philosophy in Plato and Nietzsche. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Sario, N.A. (2015) Nietzsche’s Self-Actualization Ethics: Towards a Conception of Political Self. Manila: Dunong.